LXDs use empathy to design learning experiences that meet diverse needs. By understanding learners’ motivations, challenges, and preferences through user research, surveys, and feedback, LXDs aim to build courses that truly resonate with learners and provide value.

The truth is, all people have some degree of empathy, but applying it intentionally in learning design takes practice. Before we explore how empathy can be applied through strategy and practical tools, it's worth understanding the different types of empathy and how they influence design choices.

There are three different types of empathy, each offering a distinct way to understand and connect with learners.

If you were designing a compliance course for a mid-level professional returning to work after an extended leave, you might use:

.png)

Understanding learners through cognitive, emotional, and compassionate empathy gives us insight into how they think, feel, and the support they might need.

These insights inform how we structure content, choose formats, and shape learning experiences. There are strategic design approaches and practical tools we can use to apply empathy.

Understanding the different types of empathy is a good starting point, but empathy needs to be grounded in real insight. So, how do we gather those insights and turn them into design decisions?

To design effective learning experiences, LXDs must do what we can to thoroughly examine the psyche of the learner. To fully empathise with learners, we must understand their motivations, fears, and aspirations, and how their lived experience shapes their journey. To get this information, you can:

Go beyond surface-level information by conducting interviews or focus groups to understand learners’ motivations, assumptions, and lived experiences. This might not always be possible with time, budget, or access constraints, but you can start small – sometimes, one meaningful conversation reveals several assumptions.

Complement broader insights with research that focuses specifically on how learners interact with specific courses or content. This research can include usability testing, surveys, or pilot sessions to uncover engagement patterns and friction points. For example, you might discover that a particular learner group tends to drop off during long sessions, signalling a need for shorter, more flexible learning formats.

Use data analytics to track key metrics like completion rates, time spent on tasks, and assessment scores to identify areas where learners struggle or disengage. Real-time feedback from LMS analytics, engagement data (e.g., video views, clicks), and survey responses provide valuable insights into learner behaviour, allowing for ongoing adjustments to improve content relevance and effectiveness.

Build a persona using the insights you’ve gathered, including personal motivations, learning barriers, and context (e.g., work-life balance, tech access, prior experience). Use this persona to guide your design decisions by asking:

The answers to these questions should directly influence your design decisions – from content length and pacing, to format choices, accessibility considerations, assessment design, and support mechanisms.

Empathy is powerful at the individual level, helping us understand what drives learners, where they might struggle, and what support they need to thrive. But how do we scale that empathy across diverse learner groups? That’s where Universal Design for Learning (UDL) comes in.

UDL is a framework that emphasises creating flexible learning environments that accommodate a wide range of learners, regardless of their individual preferences or abilities. It encourages designers to build in multiple ways for learners to engage with content, process information, and demonstrate understanding.

UDL is especially valuable in large-scale or open programmes, such as professional certifications or Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), where detailed audience insights may be limited. In these contexts, empathy means anticipating variability and designing for choice – for example, offering multiple formats, flexible pacing, and varied assessment approaches.

When working with smaller or more defined learner groups, UDL still applies, but it can be complemented with deeper personalisation informed by learner research and personas.

In both cases, UDL provides the foundation: it ensures that accessibility, inclusivity, and flexibility are not add-ons, but core design principles – regardless of audience size.

The way learners interpret content is heavily impacted by their backgrounds, values, and culture, as well as personal experiences and societal influences. What resonates with you might not resonate with the learners. If we ignore diversity, we risk creating content that disengages learners, but also reinforces stereotypes or causes harm.

Consider how learners from various cultural backgrounds can perceive a single piece of content differently. For example, in a cybersecurity course I recently encountered, a multiple-choice question presented a scenario involving a ‘covert terrorist cell’:

‘A covert terrorist cell, led by an individual named Ahmed, needs to move the funds they have accumulated to different locations. Which of the following actions would be an example of the moving stage in the terrorism financing process?’

What are your first thoughts when you read this scenario? How does it make you feel? How do you think it might make others feel?

This scenario wasn’t just culturally insensitive – it also undermined the learning objective. The content could test the same concept without the stereotype. When crafting learning experiences with empathy, it’s important to consider how every element – scenarios, metaphors, imagery, and examples – might land with learners from different cultural backgrounds. Do these things elevate the content and make it more ‘sticky’, or do they distract, confuse, or even possibly offend the learner?

While we all want to make content more relevant and engaging, sometimes conveying a point more neutrally is the answer.

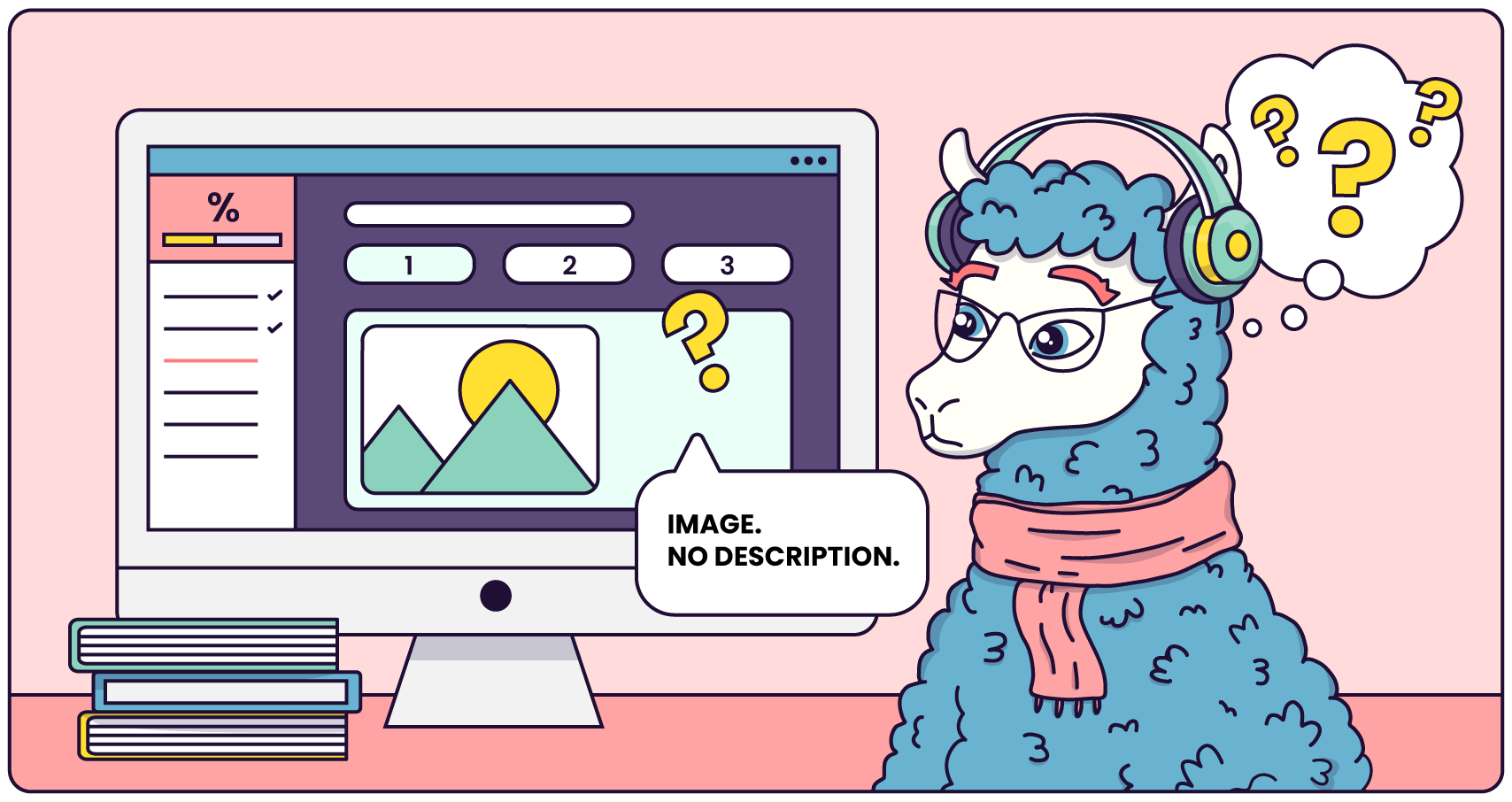

Let’s consider another example. Imagine a course assessment that asks learners to study an image and describe the error they see in a text box below. At first glance, this might seem like a straightforward way to test understanding, but the task relies entirely on visual interpretation, with no alternative description or explanation provided.

For visually impaired learners, this task would be impossible to complete. Without providing an alternative format – like descriptive text or an audio explanation – the activity becomes a barrier to participation rather than an opportunity for learning. This could make the learner feel confused, frustrated, and excluded. Empathy in design means considering the diverse needs and experiences of all learners. That includes making sure that every learner can fully engage and complete all the activities you create.

By anticipating potential exclusion points and offering inclusive alternatives, we create space for every learner to feel capable, considered, and supported.

These strategic approaches provide the frameworks needed to ground empathy thoughtfully and at scale. To put them into practice, let's explore how UX design and design thinking can help LXDs apply insights iteratively, test assumptions, and refine the experience to better meet learners’ needs.

Borrowing insights from Design Thinking – a problem-solving approach that prioritises human needs through iterative testing – and UX can help us develop a more human-centred approach to LXD. These methodologies offer actionable strategies to build more inclusive and engaging learning environments. Here are five practical tools to apply in your learning design practice:

Designing with empathy also means considering those who support learners, particularly facilitators, because impactful learning isn’t just about transferring knowledge; it’s about creating connections where learners feel truly seen, heard, and valued.

While our primary focus is often on learners, we must also extend our empathy to facilitators and instructors. They are the ones who bring our designs to life and interact with learners on a day-to-day basis. Understanding their needs, challenges, and perspectives can lead to a more cohesive and supportive learning environment.

Facilitators often juggle multiple responsibilities, from delivering content and providing feedback to managing classroom dynamics and supporting learners' individual needs. By empathising with their experiences, we can design resources and support systems that help them thrive in their roles.

For example, consider an online degree programme where facilitators are faced with the challenge of managing large classes. An empathetic design approach might include tools like automated grading, peer review systems, and streamlined communication channels. Automated grading tools can handle routine assessments, freeing facilitators to focus on providing meaningful feedback. Peer review systems can foster learner engagement and reduce the grading load. Streamlined communication channels can improve interaction between facilitators and students, making it easier to manage large groups.

Supporting facilitators through thoughtful design helps them deliver content more effectively and consistently. This enriches the learning experience for students and fosters a more connected and responsive learning environment.

Empathy helps us move beyond assumptions and generic solutions. It builds trust, reduces barriers, and creates learning that feels human and inclusive. So, as you reflect on these strategies, ask yourself:

Pick one empathy strategy and test it in your next project. The more we design with empathy, the more impactful, inclusive, and meaningful our learning experiences become. Your learners will feel the difference, and so will you.

Which strategy are you going to try first?